I am not the most positive person in the world. I would describe myself as a realist but I've heard others saying I am negative. Be that as it may, I don't like to call good evil or evil good. I don't want to delude myself in any way, shape or form. That is both a blessing and a curse. It's a blessing because I avoid disappointment and it's a curse because it blinds me to a reality beyond my reality. It can be quite a struggle to summon up faith or gratitude for someone predisposed to making decisions based on facts alone. By that I don't mean being optimistic. Optimism was never and will never be a goal for me. Having a grateful heart and holding onto faith that's what I am after. Optimism gets you nowhere.

There is a book, 'Good to great' by Jim Collins. In it, the author is interviewing Admiral James Stockdale, the highest ranking officer in US military to be imprisoned in the Hanoi Hilton (1965-1973). He asks the Admiral, “Who didn't make it out?” “Oh, that's easy,” said Stockdale. “It was the optimists. The optimists were the ones who said, “we're going to be out by Christmas. Christmas came and went. Then they'd say, “we're going to be out by Easter” and Easter would come and it would go. The optimists would pin their dates on Thanksgiving, then Christmas again, and eventually “they died of a broken heart”.....

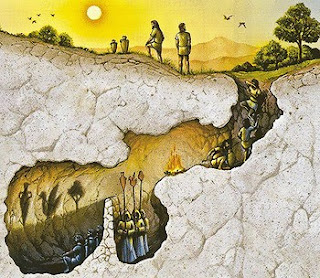

“You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end. Instead you need to confront the the most brutal facts of your reality, whatever they might be.”When it comes to this faith I've placed wholeheartedly in Jesus Christ, I am not some blind fool that is being led by wishful thinking. I don't believe in Him and follow Him until it feels like my feet are bleeding from trying to keep up with Him because I am an optimist. That's the last thing I am. I don't deny my present circumstances, I don't rebuke them or proclaim them away. I confront the facts. I see them for what they really are. As harsh, as scary and unmovable as they may be, I don't close my eyes and pretend I'm in a happy place. The last thing I need is for anyone to 'bring me down to earth'.

So no, I am not an optimist. I have faith. Not that things will be good for me. I have faith that He is good. My faith is not in some blissful future that He has for me because I follow Him. My faith is in Him that has crossed the heavens to make me His and come hell or high water will not let go of my hand until He gets me home safely. My hope is that all things work together for the good of those that love Him, even if I fail to recognize that good for what it is.

Corrie Ten Boom and he sister Betsie were two Christian Dutch women who helped harbor Jews from the Nazis in Holland during World War 2. After the sisters were arrested for doing so, they were imprisoned at Ravensbruck, a German concentration camp. The barracks they were assigned to were so awful that it almost broke their spirit. So awful in fact that Betsie died because of the conditions in those barracks. Now, there were no great barracks in any of the camps to be sure, but those that Corrie and Betsie were in had an extra blessing. Fleas. Those drove Corrie crazy. In an attempt to lift her spirit, Betsie tells Corrie to open the Bible they had smuggled in, and turns to 1 Thessalonians 5:14-18, “Comfort the frightened, help the weak, be patient with everyone. See that none of you repays evil for evil, but always seek to do good to one another and to all. Rejoice always, pray constantly, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus …” “That’s it!” Betsie interrupted. “That’s His answer. ‘Give thanks in all circumstances!’ That’s what we can do. We can start right now to thank God for every single thing about these barracks!”

Corrie stared at her incredulously, then around at the dark, foul-smelling room. “Such as?” she inquired.

“Such as being assigned here together.”

Corrie bit her lip. “Oh yes, Lord Jesus!”

“Such as what you’re holding in your hands.”

Corrie looked down at the Bible. “Yes! Thank You, dear Lord, that there was no inspection when we entered here! Thank You for all the women, here in this room, who will meet You in these pages.”

“Yes,” agreed Betsie. “Thank You for the very crowding here. Since we’re packed so close, that many more will hear!” She looked at her sister expectantly and prodded, “Corrie!”

“Oh, all right. Thank You for the jammed, crammed, stuffed, packed, suffocating crowds.”

“Thank you,” Betsie continued on serenely, “for the fleas and for …”

That was too much for Corrie. She cut in on her sister: “Betsie, there’s no way even God can make me grateful for a flea.”

“Give thanks in all circumstances,” Betsie corrected. “It doesn’t say, ‘in pleasant circumstances.’ Fleas are part of this place where God has put us.”

As the weeks passed, Betsie’s health weakened to the point that, rather than needing to go out on work duty each day, she was permitted to remain in the barracks and knit socks together with other seriously-ill prisoners. She was a lightning fast knitter and usually had her daily sock quota completed by noon. As a result, she had hours each day she could spend moving from platform to platform reading the Bible to fellow prisoners. She was able to do this undetected as the guards never seemed to venture far into the barracks.One evening when Corrie arrived back at the barracks Betsie’s eyes were twinkling. “You’re looking extraordinarily pleased with yourself,” Corrie told her.

“You know we’ve never understood why we had so much freedom in the big room,” Betsie said, referring to the part of the barracks where the sleeping platforms were. “Well—I’ve found out. This afternoon there was confusion in my knitting group about sock sizes, so we asked the supervisor to come and settle it. But she wouldn’t. She wouldn’t step through the door and neither would the guards. And you know why?” Betsie could not keep the triumph from her voice as she exclaimed, “Because of the fleas! That’s what she said: ‘That place is crawling with fleas!’ ”

You see... this irrational faith God has given us, is not for a happily ever after on earth. It has nothing to do with how good or how bad things work out for me. Even as I write this I have prayers before my King that He will work a miracle. I wish it more than anything I've wished and I have wished for a great many things in my life. But whether He does as I've asked Him or not, it doesn't change the way I see Him, love Him or follow Him. He is worth a tear or two, a broken heart or a missing limb.

There is a Romanian Christian song that my mom used to sing and it says, 'Lord, may I never be able to let go of You, even if I have to leave a buried love every step of the way.'

I

hate pain. I hate loss. I hate suffering. I hate the fleas. I don't

see their purpose. They are just an extra thing to torment me on top

of many other things. But maybe... Just maybe, the fleas are a blessing in disguise.

By Cristina Pop

.jpg)