I have always wished to be wise. Always. Having said that, I don't mean that I didn't wish for anything else. Oh, I have wished for a great many things at different stages in my life.

My first wish ever had been for my grandmother to live forever. I must have been around five years old when I wished for that. When I was seven, I wished to forget having followed a line of tanks during what was the 1989 revolution in Romania. Until I was about ten years old, I wished to feel as free as everybody else. We were not Communists anymore. We were free. I didn't even know what that meant, but they were saying it on the TV, in schools, in churches and I just didn't see it, let alone believe it, so yeah, I wished to feel free. When I was about twelve, I wished to be someone else, someone better than I perceived I was. When I was about fourteen, I wished with all my heart to be beautiful and I very much feared I was not. When I was about fifteen I wished with all my heart to be rich. By that I don't mean having a yacht and a chauffeur. I didn't know how to imagine that, but I wished to never lack anything. To me that was rich. When I was about sixteen I wished to be a great singer and I was heartbroken to find out I couldn't even hold a tune. When I was eighteen I wished to stop being afraid. When I was in my twenties I wished to be loved. After thirty I wished to be able to love myself. But regardless of how many things I have wished for in my life, I have always wished to be wise.

I remember being a child and hearing about King Solomon and how he had prayed for wisdom and God had granted it to him alongside riches and everything else. I thought to myself, 'that's what I want!'. So I began praying for wisdom and didn't understand why I wasn't wise. Then I started thinking that God sees all things and He saw that in my heart of hearts I had prayed for wisdom only to get everything else alongside with it and He must have despised my cunning nature, that's why I was as obtuse as they come.

I feared stupidity and ignorance more than anything. Well, not quite. I feared snakes more than I feared stupidity. But still, the point is I didn't want to be stupid.

For the longest time I thought that wishing to be wise was the same as being wise. I had thought that my part was simple. Wish for it and pray for it and miraculously I would become wise. I even added faith to my prayers to ensure I would be extra-wise. I had so much faith that I could envision myself being this guru-like figure that people would seek advice from and marvel at how wise I was. There is a Romanian saying, 'the fool who is not proud, is not foolish enough' and I could have been the poster-child for that saying. It took me many years to understand my own foolishness.

If wisdom would be so easily attained, then the entire world would be wise. I would be wise by now. But instead I had to first understand that wisdom doesn't come by way of an angel coming from heaven and touching my forehead declaring in a loud voice, 'behold, now thou art wise!' I began pondering the possibility that maybe wisdom is something you seek continuously. But how to seek and where? Is it limited only to some people or can anybody become wise? Does wisdom engage only one's ability to reason and accumulate information about important things or is it more than that? Does it suffice for one to be above average intellectually speaking? If so then there is no hope for someone like me and I refuse to accept that regardless of how ridiculous I might sound.

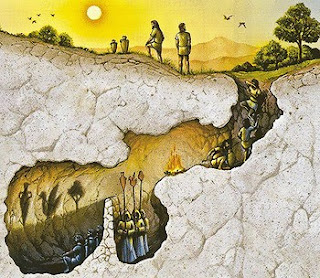

In Plato's book The Republic there is an image that has helped put things into perspective for me. The scene is set as a discussion between Socrates and Glaucon. Socrates begins by asking Glaucon to imagine a cave-like dwelling under the earth. There are people living in this cave since their childhood, shackled by their legs and necks in such a way that the only thing they can see is the wall in front of them. Because they are shackled they cannot turn their heads around but they do have a little bit of light coming from a fire that is behind them at some distance. Between the fire and the prisoners' backs there are statues and puppets paraded by puppeteers. Some puppeteers are speaking and some are silent. Whatever is paraded in front of the fire casts huge shadows on the wall that the prisoners see and whatever noise they hear behind them they imagine it comes from the shadows they see. Socrates continues to ask Glaucon to imagine what it would be like if any of the prisoners was to be unchained, made to stand up, turn around, walk and look up toward the light. The prisoner would be able to do all that only with great pain. The light would hurt his eyes and would be unable to look at those things whose shadows he previously saw. What would he say if someone were to inform him that whatever he thought he saw before were mere trivialities but now he was nearer to actual beings and that now, turned around as he was, he saw things more for what they truly were? Wouldn't he be quite lost when he would see the puppets for what they were? Wouldn't he be hurting if asked to look at the glare of the fire, so much so in fact that he would wish to run back to his previous place in front of the wall wishing to go back to a state were he had felt so sure of everything known to him? And if he decided to continue wouldn't he decide that whatever he saw now, regardless of how fantastical it might seem, was clearer to him than what he had previously saw? Glaucon agrees. Socrates continues his parable by asking Glaucon to imagine still what it would be like if the prisoner would be dragged outside, even by force and made to look at the world outside the cave. The prisoner would be in pain and in rage at his plight but after a while, after his eyes would get accustomed to the light, he would begin to see the things around him and draw conclusions about the sun and its function. Now once he has seen all these things the prisoner might start to remember the cave and what passed for wisdom in the cave and feel sorry for the other prisoners. “However, what if among the people in the previous dwelling place, the cave, certain honors and commendations were established for whomever most clearly catches sight of what passes by and also best remembers which of them normally is brought by first, which one later, and which ones at the same time? And what if there were honors for whoever could most easily foresee which one might come by next? Do you think the one who had gotten out of the cave would still envy those within the cave and would want to compete with them who are esteemed and who have power? Or would not he or she much rather wish for the condition that Homer speaks of, namely "to live on the land [above ground] as the paid menial of another destitute peasant"? Wouldn't he or she prefer to put up with absolutely anything else rather than associate with those opinions that hold in the cave and be that kind of human being?

GLAUCON: I think that he would prefer to endure everything rather than be that kind of human being.

SOCRATES: And now, I responded, consider this: If this person who had gotten out of the cave were to go back down again and sit in the same place as before, would he not find in that case, coming suddenly out of the sunlight, that his eyes ere filled with darkness?"

GLAUCON: Yes, very much so.

SOCRATES: Now if once again, along with those who had remained shackled there, the freed person had to engage in the business of asserting and maintaining opinions about the shadows -- while his eyes are still weak and before they have readjusted, an adjustment that would require quite a bit of time -- would he not then be exposed to ridicule down there? And would they not let him know that he had gone up but only in order to come back down into the cave with his eyes ruined -- and thus it certainly does not pay to go up. And if they can get hold of this person who takes it in hand to free them from their chains and to lead them up, and if they could kill him, will they not actually kill him?

GLAUCON: They certainly will.” (Republic, VII 514 a, 2 to 517 a, 7 - Translation by Thomas Sheehan)

I think I was in my twenties when I first heard about this allegory and I remember thinking, 'I am definitely the prisoner who has seen the light!' My first clue about my own stupidity or pride or both should have been quite obvious. But it wasn't. It took me a very long time and even to this day I am still accepting the fact that I am just one who sits in the cave forming opinions about the shadows on the wall. No doubt that any person of science will imagine that those in ignorance of his science are the prisoners. Any philosopher will feel that he has seen outside the cave and those that don't understand the depth of their philosophy are prisoners. Any man of faith will imagine that their belief has set them free and the unbelievers are the prisoners. We're funny like that. I'm funny like that. Nobody likes to admit to their own limitations. We like to think we draw the right conclusions whenever we assess anything we deem important. I want to know that I am not wrong about the important things in life. I want to believe I see things now as they will be forever and I forget I am only seeing shadows on a wall. Sometimes I argue or even debate about whatever I see passing before me. I can't see properly and most of the times I am not even aware of my own lack of sight. I only know the other prisoners by their loud or timid voices. I band together with those whose opinions I share about certain shadows and I hate those who disagree. I am ignorant of certain shadows on the wall because I can't see everything from where I stand and envy those that have a better spot. I judge prisoners as successful or failures by how much dirt they manage to gather with their shackled hands. I study about what other prisoners have turned into science by observing the height of the shadows and the noises we think are coming from them. I cower in fear whenever the shadows change their pattern and rejoice when they are acting according to my expectations and call that 'divine inspiration'. I bow in respect to whatever passes for knowledge and scuff in disgust like a good prisoner at anything that doesn't make sense to me without even considering the possibility that I might be wrong. I am afraid of questioning the shadows because I don't want to be weirder than I already feel. There are endless theories made by prisoners concerning the shadows and even the wall; philosophies about our purpose in the cave and even accounts of some who claim to have been freed and went outside and I don't know how to distinguish truth from fantasy. After all I am not wise. I fear to even listen to the 'lunatics' that claim they have been outside the cave when I am not even convinced we are in a cave in the first place and that the ornaments around our legs and necks are shackles.Would

I go so far as to kill one that would come to preach salvation from

my cave? I like to think not, but I already have. If not in deed then

certainly in spirit. The Son of God.

I don't like anything that feels like it's about to attack my 'values'. I am a proud prisoner after all, ignorant of my cave. I like to imagine that whatever I happen to believe at any given time is the 'right thing' by the very fact that it is I who believes it. I leave no room for maybe because uncertainty scares me. I need things to be in black or white and whenever I make room in myself even for a little gray I feel like the most liberal-thinking person on earth. So of course I want to kill whoever wishes to oppose my carefully crafted opinions because it feels that by questioning them the one issuing the oppositions is trying to kill me. For all the love I preach, it is an eye for an eye after all. Well in my case an eye, an arm, a lung and the liver for one questioned theory. Is there any hope for me?

So I begin reflecting about everything I feel is important from my cave and whoever reads this should take everything I say with a grain of salt because the only thing I know for a fact is like Socrates, that I don't know anything. Whatever conclusions I might reach are bound to be flawed in some way first by my own ability to reason perfectly and second by the very narrowness of my circumstances. But deep down inside I feel that my current condition is not all there is. I feel there must be something else, something I can't see which makes me doubt. And doubt is uncomfortable so I try my best to find something to distract me. A little stone that crawled as by divine hand all the way to me, a stick, anything, just to forget and keep watching the wall. After all it's wise to watch the wall carefully and learn the patterns. And I do wish to be wise. by Cristina Pop

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment